- Home

- India

- World

- Premium

- THE FEDERAL SPECIAL

- Analysis

- States

- Perspective

- Videos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- Elections

- Features

- Health

- Business

- Series

- In memoriam: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

- Bishnoi's Men

- NEET TANGLE

- Economy Series

- Earth Day

- Kashmir’s Frozen Turbulence

- India@75

- The legend of Ramjanmabhoomi

- Liberalisation@30

- How to tame a dragon

- Celebrating biodiversity

- Farm Matters

- 50 days of solitude

- Bringing Migrants Home

- Budget 2020

- Jharkhand Votes

- The Federal Investigates

- The Federal Impact

- Vanishing Sand

- Gandhi @ 150

- Andhra Today

- Field report

- Operation Gulmarg

- Pandemic @1 Mn in India

- The Federal Year-End

- The Zero Year

- Science

- Brand studio

- Newsletter

- Elections 2024

- Events

- Home

- IndiaIndia

- World

- Analysis

- StatesStates

- PerspectivePerspective

- VideosVideos

- Sports

- Education

- Entertainment

- ElectionsElections

- Features

- Health

- BusinessBusiness

- Premium

- Loading...

Premium - Events

How a tiny temple became BJP’s big tool for renaming Hyderabad

What’s in a name? Apparently, a lot if the BJP sets its mind to renaming a place. After the BJP’s impressive show in the recent Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation (GHMC) elections — winning 48 of 150 seats — the party has renewed its push to rename Hyderabad as Bhagyanagar. The renaming attempt assumes more significance since the BJP’s strength is just 8 less...

What’s in a name? Apparently, a lot if the BJP sets its mind to renaming a place.

After the BJP’s impressive show in the recent Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation (GHMC) elections — winning 48 of 150 seats — the party has renewed its push to rename Hyderabad as Bhagyanagar.

The renaming attempt assumes more significance since the BJP’s strength is just 8 less than the 56 seats won by the ruling Telangana Rashtra Samithi (TRS) Party and more than the 44 wards won by the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM), whose stronghold is the Old City.

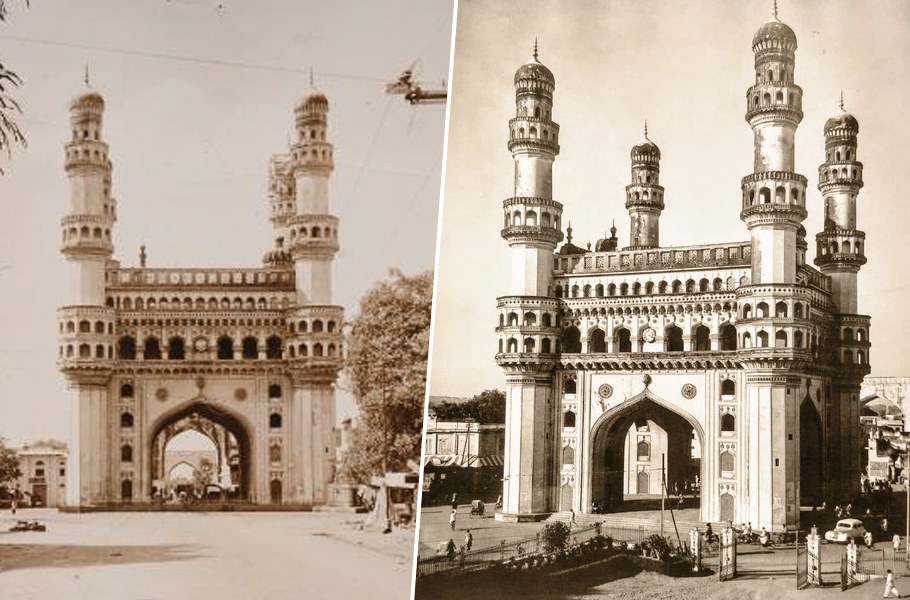

Changing the names of places is a state subject. However, what adds strength to the BJP’s claim is the visit by a battery of the saffron party leaders to the Bhagya Lakshmi temple, adjacent to one of the minars (pillars) of the 430-year-old historic Charminar. In fact, the party attributes the name ‘Bhagyanagar’ to the temple.

The history and the controversy

While Muslim intellectuals assert that Hyderabad was never called Bhagyanagar and that the Bhagya Lakshmi temple came into existence only sometime after the 1970s, Hindu leaders claim that the temple was in existence much before the Charminar was built in 1591. They claim that the monument was built on the place where the temple existed.

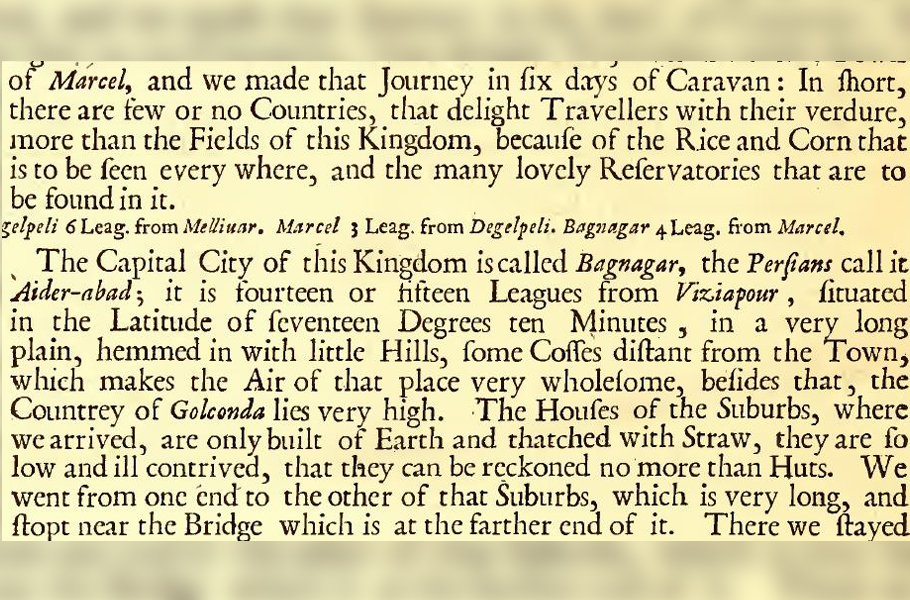

But according to historic references available, the city, right from day one of its formation, has been known as Hyderabad. Some say it was also called Bagh Nagar — ‘city of gardens’. Some others called it Bhag Nagar, which loosely translated means ‘city of fortune’.

It was called the ‘city of gardens’ because of the beautiful orchards and hanging gardens adorning the city. For instance, the Qutub Shahi palace had huge hanging gardens. One of the gardens extended from the present Hussain Sagar Lake to the Chaderghat Bridge on one side and, on the other side, it extended up to Hakimpet, beyond Alwal.

The huge garden was known as Bhag-e-Dilkusha. Because of this, French traveller Thevenot, who visited Hyderabad during the period of Abdullah Qutub Shah VII, described Hyderabad as the city of gardens, or Bagnagar (Baghnagar).

In one of the references, he said that while Muslims call it Hyderabad, Hindus call it Bhag Nagar, city of fortune, perhaps owing to gold, pearls and diamonds sold in the Golconda streets. It was the centre of diamond and pearl trade. Five of the top 10 diamonds mined in the world come from the Qutub Shahi kingdom.

The love story

According to a legend, Mohammed Quli Qutub Shah, who founded Hyderabad, was in love with a village girl called Bhagmati. Because of his love for her, Qutub Shah named Hyderabad as Bhagyanagar. This though is only a legend, and not a historical fact.

To understand the lore of Bhagmati, one has to go back into history. The first ever reference to Bhagmati was made by Mohammad Qasim Hindu Shah, who was also known as Farishta. In his History of Hindustan, he mentioned that Quli Qutub Shah was in love with a girl named Bhagmati. That was the earliest reference to Bhagmati and it is more than 400 years ago.

Another reference could be found in the writings of Abid Ali Khan, the founder of The Siasat Daily (Urdu daily), and Urdu author and reformist Moinuddin Ahmed Joar. They, in fact, found a grave said to be that of Bhagmati, in Yakutpura area of the city. So, whether Bhagmati existed for real is a disputed fact.

Some believe that she was a real person. Others are sure that she was a mythical character.

The latest argument put forth by the right-wing and Hindutva leaders is that there was a temple dedicated to goddess Bhagya Lakshmi at the spot where Charminar stands. Because of Bhagya Lakshmi, the city was called Bhagyanagar.

The Archeological Survey of India (ASI), however, has concluded that the temple surfaced sometime between 1959 and the 1980s. In 2013, responding to an RTI query, the ASI called the temple an unauthorised construction. It also furnished three photographs from its archives — one taken in 1959, the second in 1980s and the third in 2003, according to a 2013 Times of India report.

In the photograph from 1959, there is no structure visible to the south eastern side of Charminar. But the one from the early 1980s shows the temple. This indicates that the temple did not predate the Charminar as argued by Hindu groups.

M Rama Raju, president of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) Telangana unit, disputes the ASI version. He tells The Federal, “Bhagya Lakshmi temple existed before the Charminar was built in the Quli Qutub Shah period. In 1908, most parts of the city were washed away and a large number of people died in floods. On the advice of a minister called Prasad, the Nizam offered a saree, a nose ring and a Sare (a presentation comprising many things) to the Goddess, observing Hindu customs. The flood receded.”

This, he claims, is the ‘great history’ of the temple. “Hindus have been worshipping there for centuries, offering Bonalu (food offered to the Goddess in Aashadha masam (Telugu month generally falling in July-August). We are digging out old documents to confront the argument of the Archeological Survey of India.”

Photographs and videos taken in the 1940s and 50s, however, do not show the Bhagya Lakshmi temple at the location where the Charminar stands. The temple could be seen in photographs taken after the 1970s, though. It is attached to the Southeast minar (pillar) of the Charminar. The pillar serves as the back wall of the temple made of bamboo poles and tarpaulin with a tin roof.

City historian and Shia religious scholar Ejaz Farruq, 72, remembers how Bhagya Lakshmi temple came up sometime after 1976.

“There were four boulders on four corners of Charminar serving as crash guards. This was to prevent damage to the minarets in case a vehicle rams into the monument. The entire load of the Charminar rests on the minarets.

Some people put up a green flag and used to put turmeric and tilak to the pillar every day.

“In 1976, a double-decker bus hit the Southwest pillar, damaging it. Sentiments of the people were hurt. A Marwari jeweller, associated with the Jana Sangh, is said to have funded the new idol. And this is how the temple came up.”

Farruq also sheds some light on the popular love story. “Primarily, the talk of renaming Hyderabad as Bhagyanagar comes from the belief that Qutub Shah was in love with a girl called Bhagmati. It was a very romantic tale. But should we go by tales and keep changing the names of places?” he asks.

“Hyderabad was never called Bhagyanagar. If at some point in history it was called so, then there may have been some justification for demands to rename it. Let those people who time and again make this demand tell us. When was it called Bhagyanagar and who changed the name?”

Hyderabad, he contends, is a city built in 1591 and called so from day one.

No mention of it in coins, too

The coins minted during the Qutub Shahi regime after the formation of Hyderabad can be considered as another historic check. The oldest coin minted by Qutub Shah had the name Hyderabad inscribed on it. But there was no mention of Bhagyanagar, or Bhag Nagar, or Bagh Nagar.

Qutub Shahis were Shias. They regard Hazrat Ali as second to Prophet Mohammad. The city was founded coinciding with the 1,000 years of Islam in 1590-91. So, they named the city as Hyderabad. Hyder (lion), was the title given to Hazrat Ali, the son-in-law of Prophet Mohammad. Hyderabad, thus, means the city of lions.

According to one theory, to commemorate that celebration, they built Charminar as a grand monument.

There is another theory related to the outbreak of plague during the period that claimed many lives. It is believed the plague had subsided after Muharram. To commemorate the victory over the disease, Charminar was built at the very spot where the sacred Tazia (replica of the coffin of Imam Hussein) was kept during Muharram.

Another theory says this was the place where Qutub Shah met Bhagmati. She was from Chichalam village near Shali Banda, a little away from Charminar and Mecca Masjid.

The legend goes: He used to cross the Musi river to meet her. Once when there was a flood, he could not cross the river and his father, Ibrahim Quli Qutub Shah, built the Puranapul bridge. This is why it is also called the bridge of love. But, what makes it unbelievable is the fact that Mohammed Qutub Shah was only 11 then.

Strangely, stories related to Bhagmati end abruptly and there isn’t much anywhere about her marriage or children.

At Qutub Shahi tombs, there are the graves of kings and queens and their children. Old timers contest if Bhagmati was a real character, her grave should have been there. Especially since the tomb of Bhagirathi, a Hindu princess from the Vijayanagar empire who was married to Ibrahim Quli Qutub Shah, lies there.

Hence, some believe that Bhagmati was a fictional character. Many others still argue that she cannot be considered fictional merely because of the absence of her grave.

Moreover, Hyderabad is a city built from scratch. All Qutub Shahi structures form the first layer of construction in Hyderabad.

The name Bhagyanagar, many others claim, got popular only in the 1960s, several years after the merger of Hyderabad with the Indian Union in what was described as the ‘Police Action’ in 1948.

Small temple, big politics

The temple is small in structure but, of late, has emerged as very powerful, politically. BJP state president Bandi Sanjay in November took an ‘oath of truth’ at the temple following allegations that he wrote to the state election commission to stop the distribution of Rs 10,000 financial aid to families who suffered losses in the floods the previous month.

The ruling TRS had alleged that Sanjay halted the distribution by making a complaint to the election commission.

In December last year, Union Home Minister Amit Shah visited the temple before embarking on a campaign for the GHMC polls. His deputy G Kishan Reddy, who hails from this city, visited the temple many times.

Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath hinted at renaming the city, saying, “Several people ask me if Hyderabad can be renamed as Bhagyanagar. I tell them why not.”

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s brother Prahlad Modi, too, visited the temple in the last three months.

Bollywood actor Govinda’s wife Sunita Ahuja and Tollywood actress Payal Rajput are among some of the celebrities who visited the temple.

Notably, after being elected as the mayor, TRS leader Gadwal Vijaya Lakshmi visited the Bhagya Lakshmi temple before assuming charge in February.

Apart from the political rhetoric involving the temple, it draws huge crowds on Fridays and during festivals. The rush of visitors, however, is normal on regular days. Following incidents of clashes and stone pelting in the past, a round-the-clock two-tier security arrangement was put in place.

A multi-queue complex was erected to regulate access to the sanctum sanctorum, after the temple witnessed three big clashes. There was an attack on the temple in November 1979, when the AIMIM called for a bandh. In September 1983, there were reports of disturbances after activists put up banners for Ganesh festival.

Again in November 2012, there were clashes over the temple committee’s purported attempts to erect a permanent shed, in place of bamboo structure.

In 2013, the high court directed the police to ensure that the temple complex does not expand any further, after it was alleged that it was extending the boundaries by a little every now and then.

According to the temple priest, “Normally, the situation is peaceful. Devotees come, pray and go. Earlier, disruptive elements used to try create disturbances.”

But with demands to rename the city growing louder, it seems only a matter of time before the controversy assumes an Ayodhya-like proportion.