Modi’s largesse for Purvanchal exposes BJP’s faultlines in poll-bound UP

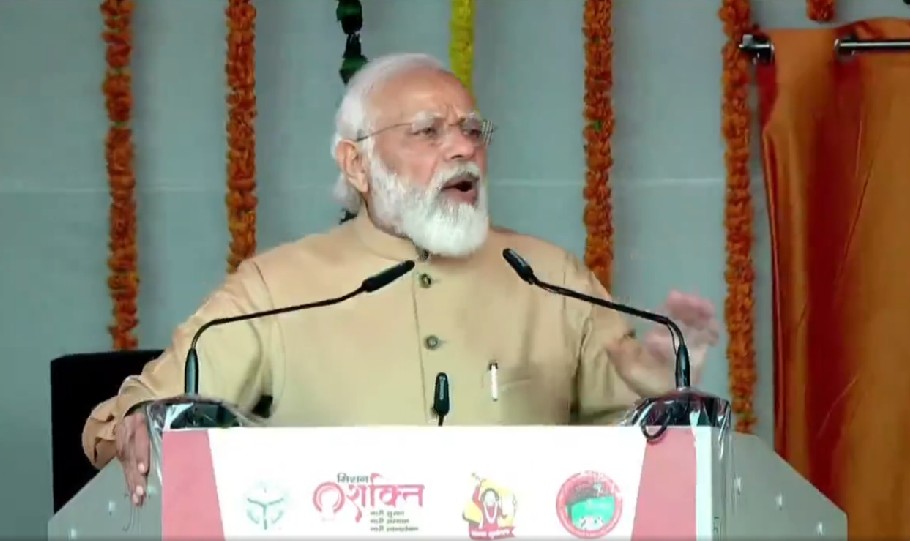

Prime Minister Narendra Modi is, once again, in eastern UP (Purvanchal) on Wednesday, December 21, with his bottomless sack of endowments for people of the poll-bound state.

Modi’s interaction at Allahabad’s Parade Grounds with 2.5 lakh women beneficiaries of sundry government schemes and his announcement of further largesse for the state marks his third visit this month to Purvanchal.

Last week, Modi was on a two-day visit to his Lok Sabha constituency of Varanasi, a little over 120 kms from Allahabad, to inaugurate the first phase of the Kashi Vishwanath Dham Corridor project.

Prior to this, he had visited Gorakhpur, the political bastion of Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath, on December 7, to launch a slew of development projects for Purvanchal, including the Gorakhpur centre of AIIMS.

With crucial assembly polls due in the state in February-March 2022, Modi’s frequent dashes to UP are understandable. However, what stands out about Modi’s recurring UP darshan is his obvious focus on Purvanchal — a region that constitutes some of the most economically backward districts of UP — at a time when the BJP’s toughest electoral challenge in the state has, arguably, been brewing on UP’s western flank where wounds inflicted by the Centre’s now-repealed farm laws are still festering.

At first glance, there is nothing unusual about this incessant windfall and the accompanying publicity blitzkrieg. Successive ruling parties and their principal mascots — be it in the states or at the Centre — have adopted, to varying degrees, the practice of reserving the inauguration or promise of big ticket projects for their electorate to the last quarter of their term in office. Modi, and Yogi, are doing the same.

A sea of women welcome PM @narendramodi ji today at Prayagraj pic.twitter.com/MpsV3exZqg

— Shehzad Jai Hind (@Shehzad_Ind) December 21, 2021

A closer look, however, unravels the pragmatic electoral arithmetic behind this aggressive courting of Purvanchal voters. It also betrays a degree of nervousness within the saffron camp over the changing trajectory of politics in this region that accounts for over 130 of UP’s 403-assembly seats.

“Anti-incumbency in Purvanchal is palpable and it is growing; the government’s massive publicity drive is only angering the voter further… while there has been visible progress on the infrastructure front, people are upset over the government’s failure in making their daily lives better because inflation, petrol and diesel prices, unemployment, stray cattle wreaking havoc on agricultural activity are all worse than five years ago,” says Harsh Sinha, a professor at the Gorakhpur University and commentator of Purvanchal’s socio-political activities.

Over the past two months, eastern UP — the political karmabhoomi Modi adopted over his home state of Gujarat following the BJP’s 2014 Lok Sabha win — has been the biggest beneficiary of the central and state government’s unending bequests. Modi has been frequenting UP since October and his every third visit has been to a district in Purvanchal.

The bounty Modi has announced on each visit by way of mega projects — some new, most only completed during the BJP’s term in office — cumulatively accounts for over Rs. 50,000 crore. These include inauguration of the Rs. 22497 crore Purvanchal Expressway (launched during the erstwhile Samajwadi Party government of Akhilesh Yadav), the foundation stone laying ceremony for the proposed Rs. 36200 crore Ganga Expressway, that will connect Meerut in western UP to Allahabad in eastern UP, nine medical colleges (six of which fall in Purvanchal) built at a cost of over Rs 2200 crore, the Rs 339 crore Kashi Vishwanath Char Dham Corridor, among several others.

Shifitng sands

In the 2017 assembly polls, the BJP had swept Purvanchal — just as it did the rest of the state — and bagged over 100 seats in the region to register its unprecedented 312 seat victory. Of course, the BJP’s 2017 success in Purvanchal was mirrored in other regions of UP too — western UP, Awadh and Bundelkhand. Nearly five years later, the sands in UP’s political landscape are shifting.

The predominantly farming community of western UP is in no hurry to forgive Modi and the BJP the excesses it braved during the peasants’ agitation that went on for 15 months before a conditional truce arrived earlier this month.

Akhilesh Yadav’s Samajwadi Party, presently seen as the only real alternative to the BJP in UP, has stitched a formidable alliance with Jayant Chaudhary’s Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD), a party concentrated in half a dozen western UP districts and one that has the region’s agrarian community as its main base.

Also read: Modi’s repeal of farm laws may not cut ice in poll-bound UP, Punjab

“Repeating its 2017 performance in Purvanchal is crucial for the BJP if it hopes to retain power in UP. As things stand today, the BJP has lost its pole position in western UP due to the farmers’ agitation. The SP-RLD alliance has the potential of reducing the BJP’s 2017 tally in west UP by half, if not more. Bundelkhand constitutes just 19 seats (the BJP had won 16 of these in 2017) but the SP is expected to perform better there too. The BJP is still strong in Awadh but to ensure that it has a comfortable majority, it needs to do well in Purvanchal. At the moment, there are no signs in eastern UP of a 2017-like wave in the BJP’s favour,” Sanjay Srivastava, professor of political science at the Benaras Hindu University, tells The Federal.

Sinha says there are several reasons that have the BJP worried in Purvanchal. “Badlaav angdai le raha hai (there is a turn for change)… price rise and unemployment affect everyone but the impact in Purvanchal is higher because the region is already economically backward; there are other micro and macro factors too… the BJP’s social arithmetic is cracking; the non-Jatav Dalits and non-Yadav OBCs who had consolidated behind the BJP don’t find any improvement in their lives and are now exploring other alternatives, and a section of Brahmins (the community is numerically strong and electorally influential in Purvanchal) is upset at Yogi’s Thakur-waad… the masses are thronging to Akhilesh Yadav’s rallies… yeh organic crowd hai jo badlaav dhoond rahi hai (this is an organic crowd that is searching for change).”

Tribhuvan Bind (53), a construction worker and native of Jhunsi on the outskirts of Allahabad, has voted for the BJP since 2014. Today, he is mobilising people in his village to vote for the SP.

What did we get — price rise and unemployment

“Kya mila hume… inka expressway khod kar apna pait bharenge kya (what did we get… will their expressways fill our stomachs),” Bind tells this reporter when asked if he was satisfied with the BJP government.

Bind concedes that his family of 11 members is a beneficiary of the free rations (chana, refined soyabean oil, salt, etc) that the state government has been distributing to the people in the aftermath of the Covid pandemic but adds promptly, “ehsaan kiya kya… sab sarkarein muft ration de rahi hain, inhone toh kaha hai ki sirf chunav tak milega (they aren’t doing us a favour, all governments give free rations and they — the BJP — are anyway going to give free ration only till the elections).”

The free rations being distributed across UP with images of Modi and Yogi plastered over the packets have, undoubtedly, been a huge draw for people in impoverished Purvanchal but the electoral benefits they may accrue to the BJP are uncertain.

Lalji Tiwari (63), who owns a paan shop in Phaphamau adjoining Allahabad, tells The Federal, “for small families, the free rations are fine but for families that have 7-8 members or more, the ration gets over in two weeks… what do you eat after that?”

Tiwari has three sons aged 40, 38 and 33 — all married and none with a full-time job. His three daughters-in-law and four grandchildren complete his family. Tiwari’s paan shop is the only regular source of income that provides for his 10-member household. Prashant and Akash, Tiwari’s elder children, worked in a garment factory in Agra but lost their job last year after the first Covid wave.

Tiwari’s youngest son Akshay, is the only member of the household to complete graduation but, for the past four years, he has been unsuccessfully trying to get a government job. “Teacher se lekar lekhpal tak, har sarkaari naukri ke liya apply kar chukka hoon par bhartiyaan ho hi nahi rahi (I have applied for every government job – from teacher to revenue clerk but the vacancies aren’t being filled),” Akshay says, adding that he takes up whatever part-time private job he can get his hands on to supplement the family’s income.

Tiwari says his entire family was ‘kattar BJP’ (staunch BJP supporters) but will vote for the SP this time. “My sons don’t have jobs. Since Covid, my income from the shop has also taken a hit… on top of this, everything has become so expensive… How do we survive? This government says there is development but what good is development if we have to starve?” Tiwari says.

The double whammy of mehangai (price rise) and berozgaari (unemployment) aside, large sections of Purvanchali voters have also not forgotten the nightmare they had to live through during the second wave of Covid earlier this year.

Abandoned in pandemic

Modi, in Delhi, and Yogi, in Lucknow, remained in denial to the chaos that the second wave unleashed across eastern UP. The UP government, in fact, went all out to control testing for the infection by placing curbs on RT-PCR tests done by private labs and hospitals curb and even cracked down on ordinary citizens who were taking to social media in droves crying for help.

The health infrastructure in UP — as in most other parts of the country — failed the people and Purvanchal faced the worst brunt in the state — dead bodies floating in the Ganga near Allahabad or buried hurriedly on the river banks and wait lists at crematoriums belied all official claims of the death toll barely ever breaching double digits in districts that fall in this part of the state.

In Lilapur village of Purvanchal’s Ghazipur district, Ram Singh Yadav (48), a farm worker tells The Federal that eight members of his extended family succumbed to Covid during the second wave and barring one, none of them managed to get admission in any hospital.

Also read: Peasants’ anger over farm laws not BJP’s only challenge in UP

In Bhandaha Kala village, on the outskirts on Modi’s constituency of Varanasi, local activist Vallabhachrya Pandey tells this reporter that there were long queues and a wait list to burn bodies of Covid victims at the hamlet’s only crematorium where ordinarily not more than two cremations take place in a week.

“In Varanasi, people were unable to get beds in hospitals or oxygen cylinders at home. There is perhaps not one family in Purvanchal which did not lose someone they knew to Covid and yet, till date, the government continues to make false claims about controlling the pandemic. Covid may not feature prominently in the electoral discourse at the moment, but many who lost their dear ones will not forget how the government abandoned them in their time of need,” Pandey says.

Chittaranjan Mishra, a professor at Gorakhpur University who is also highly regarded in the social circles of Yogi’s political fiefdom, seconds Pandey’s claims but adds a keen perspective to the politics that BJP adopted during and after the second phase.

“Under the guise of telling people what precautions they must take, the government consistently hammered down the message that it was up to individual citizens to keep themselves safe. From the PM’s speeches, government ads and even ringtones on mobile phone, you were told to wear masks and maintain social distance. As a result, people began to believe that this was an act of God and the government could do very little but was still trying to help them. The reality — the government’s healthcare infrastructure was a complete failure, no lessons were learnt after the first wave and all measures to improve the situation were taken only after the second wave subsided — was quickly masked by the government,” says Mishra.

Whether by design or not, indeed, a section of the public seems to have bought into this narrative that Mishra points at. In Varanasi, where Modi spent two nights on December 13 and 14, massive crowds had descended at the Kashi Vishwanath temple and its vicinity to see the prime minister and the entire BJP brass.

Meenakshi Sharma, a 42-year-old housewife, who came to see Modi’s mega event at the iconic temple told this reporter, “the PM warned everyone to wear masks and maintain social distance but no one followed”.

“Even today, people don’t wear masks while stepping out or keep distance from one another,” she said pointing at the massive gathering in which masked citizens were hard to spot. “The people failed our PM, they didn’t listen to him but even then he worked day and night and ensured that no one died of lack of oxygen and hospital facilities were ramped up in record time,” Sharma claims.

Brahmins oppressed

Standing in the same crowd, Abhinay Mishra, a local jeweller in Varanasi too heaped praise on Modi’s handling of the pandemic but he had a grouse against the state government — more specifically against Yogi.

“I have no complaint against Modi or the Centre, they are doing a wonderful job and the world is taking note of India for the first time,” he says, but with equal aggression insists that he will not vote for the BJP in the upcoming UP election even though he is yet to make up his mind on who he feels is a better alternative.

Mishra’s problem with Yogi signals the other big challenge for the BJP in Purvanchal — the unease within the Brahmin community against the Adityanath-led government.

“Brahmanon ne inki sarkaar banwaayi par pichle 5 saalon mei, Brahmanon ka sirf daman hua hai (the Brahmins got the BJP voted to power but in the past five years, Brahmins have only been oppressed),” Mishra says.

This Brahmin-Thakur divide is an oft-mentioned aside in any political conversation in Purvanchal. Names of gangster Vikas Dubey (killed in a suspicious police encounter near Kanpur last year) and jailed MLA Vijay Mishra, a prominent Brahmin leader and alleged mafia-don from Purvanchal’s Bhadohi, are often quoted by a section of the region’s Brahmins who believe Yogi, a Thakur, has been selectively targeting members of their community.

“We know Dubey was involved in crime and we would have supported the government if he was jailed after following proper legal procedure but the UP police gunned him down and made it look like an encounter killing because if due procedure was followed, many top BJP leaders who took favours from Dubey would have been exposed. These people accuse the SP of unleashing gundaraj but Yogi has done the same,” Radha Mohan Shukla, a local businessman in Bhadohi’s Aurai tells The Federal.

Shukla adds, “Yogi’s Thakur community has emerged as the face of UP’s gundaraj but unlike the Yadav and Muslim strongmen who got patronage of the SP during the rule of Mulayam Singh or Akhilesh, not only do people sheltered by Yogi systematically target Brahmins but even the state government oppresses members of our community through the police and some bureaucrats.”

Caste arithmetic

The BJP’s massive 2017 victory was, in great measure, a result of the continuing saffron surge across India that had begun with Modi’s rise to premiership in 2014 and a craftily stitched social coalition that saw an equitable distribution of BJP tickets to candidates from numerically significant communities among the non-Jatav Dalits, non-Yadav OBCs and forward castes like the Brahmins, Thakurs, Bhumihars and Banias.

The BJP’s social experiment of consolidating its position within its existing vote bank of the forward castes while widening its base by weaning away non-Jatav Dalits from Mayawati’s BSP and non-Yadav OBCs from the SP was further fortified through alliances with regional parties such as Union minister Anupriya Patel’s Apna Dal (Sonelal) and OP Rajbhar’s Suheldev Bhartiya Samaj Party (SBSP). Apna Dal and SBSP have small, albeit significant, pockets of electoral influence in eastern UP.

Five years on, the BJP insists that its social coalition is still intact and claims that its governments at the Centre and in UP have delivered an unprecedented model of development that has broken the tradition of appeasement of select communities that rivals such as the SP, BSP and the Congress followed in the past.

“In the five years that we have been in power, we have stuck to the Prime Minister’s vision of sabka saath, sabka vikas, sabka vishwas. UP has seen unprecedented development in the past five years… UP is being hailed as Expressway Pradesh, we have given India another model of growth and development and many are now even talking about Purvanchal model of development. Law and order has improved and so have civic amenities and infrastructure. We are confident that the people of UP will once again place their faith in us,” says Sidharth Nath Singh, minister in the Adityanath government and BJP MLA from the Allahabad (West) constituency.

Ground realities in Purvanchal, however, appear vastly different from the BJP’s tall claims of repeating its 2017 performance. To the voters in Purvanchal, the Roman poet Virgil’s epic Aeneid and its immortal line timeo Danaos et dona ferentes (I fear the Greeks, even those bearing gifts), may indeed be alien but as Modi comes bearing gifts aplenty — and with promises of many more over the next two months — this poll season, their sense of fear and suspicion cannot be grudged, or wished away. The question now is whether the BJP’s political rivals in UP have the electoral savvy to cash in on this public anger and stop the saffron juggernaut.

The SP-led coalition is, presently the most visible alternative but there are still two months before the election campaign really picks up steam — and this is a long time for a state where the political mood often changes overnight. The challenges before the SP, or other players like Mayawati’s BSP or the Congress, aren’t limited either. But that’s a tale for another day.